In January of 2024, the New York Times published an opinion piece titled ‘The End of Snow’. The timing of the article’s publication, immediately following what was labeled as the ‘hottest year ever,’ is wrapped in layers of irony. [emphasis, links added]

This scenario exemplifies the counterintuitive and often unpredictable nature of climate patterns, challenging simplistic and often unscientific narratives about global warming and its effects.

The article recounts the personal experiences of the author with changing weather patterns during the holiday seasons, contrasting memories of frigid winters with recent milder temperatures.

This serves as a springboard for a wider reflection on the implications of global warming and the future of winter as we know it, especially the phenomenon of snowfall.

From the very first moment I carved a path on the corduroy at Sierra Summit, a quaint resort nestled just outside of Fresno, California, skiing captured my heart.

Those early years, where the crisp mountain air and the exhilaration of each descent became a cherished ritual, ingrained in me a profound love for the slopes.

The mere thought that this part of my identity could be threatened by a future devoid of snow was devastating. It drove me to sift through data and expert analyses.

To my relief and somewhat vindication, I discovered that the doomsday predictions about the end of snow were overblown. While climate change is an indisputable reality, its impact on snowfall is far more nuanced than the simplistic narrative of an imminent snowless world.

On one hand, the year’s designation as the hottest on record aligns with the long-term trend of rising global temperatures since the last glacial maximum.

Such statistics are often cited as signs of a future where traditional seasons blur, and the crisp, snowy winters fade away into a warming world.

The concern that children might grow up in a world where snow is a novelty, or even a historical curiosity, reflects the profound anxiety created by the climate-industrial complex.

On the other hand, the concurrent setting of snowfall records presents a jarring contrast to these warming trends.

In 2023, ski resorts like Alta in Utah and Mammoth in California reported record-breaking snowfall totals, challenging the prevailing narrative of diminishing snow covers due to global warming.

These resorts, nestled in mountainous terrains that have long been destinations for winter sports enthusiasts, saw an unprecedented accumulation of snow that not only delighted skiers and snowboarders but also confounded expectations set by a year characterized as the hottest on record.

The copious snowfalls at Alta and Mammoth challenged simple correlations between rising average global temperatures and the decline of snowy winters, illustrating the complex and often regional nature of weather patterns and the common confusion of weather and climate by the MSM.

The sheer volume of snow, the record at Alta was more than 150 inches above the previous record, serves as a testament to the variability inherent in climate systems, and it underscores the importance of considering local and short-term climatic phenomena in the broader context of global climate change.

Snow records being set after a year that has pushed temperature boundaries is an ironic twist. It serves as a real-world reminder that while the overall trend may be toward warming, regional and seasonal extremes of cold and snowfall will still occur and even intensify in areas.

The 2024 season is still ongoing but seems to be another record-setter.

Furthermore, the article emerging at a time of record snowfall after the ‘hottest year ever’ highlights the pitfalls of exaggerating climate science to the public.

It’s a clear reminder that the language used to describe climate trends needs to be carefully crafted to avoid confusion and to help the public understand the distinction between unscientific propaganda and scientific data.

The Rutgers University Global Snow Lab delineates a fascinating snow cover trend across the Northern Hemisphere, with notable seasonal variations over the past several decades.

The first image below, representing snow cover anomalies in November, suggests a significant increase in snow cover during the autumn months. This trend might appear counterintuitive in the context of global warming.

An increase in fall snow cover can be attributed to several factors. Warmer temperatures can lead to more evaporation, and, consequently, more moisture in the atmosphere.

If temperatures in November are cold enough for precipitation to fall as snow, then this moisture can result in increased snowfall.

Additionally, shifts in atmospheric circulation patterns, such as changes in the jet stream, can also lead to greater snowfall during certain times of the year in certain regions.

In contrast, the second image shows a decrease in snow cover for May, indicating less snow cover in the spring.

The decrease in springtime snow cover is more closely aligned with the expectations of a warming climate, where the earlier onset of spring temperatures causes faster melting of winter snow.

These observed changes in snow cover—increasing in the fall and decreasing in the spring—underscore the importance of understanding regional climate dynamics within the global climate system.

They highlight that climate change’s impacts are not uniform and that shifts in seasonal weather patterns may have a variety of consequences for the natural world and human activities.

Moreover, these trends pose important questions for climate scientists, as they attempt to refine models to predict not just average temperature increases, but also shifts in precipitation patterns and extreme weather events.

For policymakers and planners, this data is critical for preparing for water resource management changes and anticipating and mitigating the impacts on agriculture, infrastructure, and ecosystems. A much better approach than climate change will likely lead to ‘The End of Snow’.

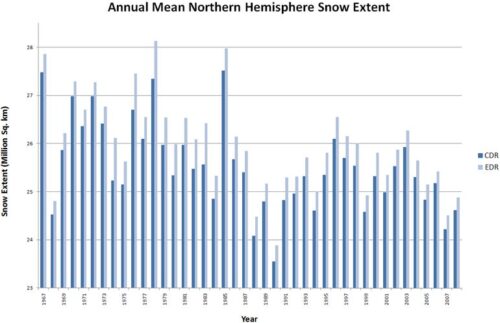

The annual mean Northern Hemisphere snow extent over several decades reveals a relatively stable pattern, indicating that despite year-to-year fluctuations, there has not been a dramatic long-term change in overall snow cover.

This stability might come as a surprise to those who assume a linear decline in snow extent due to global warming.

The data suggest that while certain regions and months may experience decreases in snowfall, overall snow cover in the Northern Hemisphere has not shown a drastic decrease over the observed period.

This underscores the complex interplay between rising global temperatures and snowfall, influenced by factors such as atmospheric moisture content and shifting weather patterns.

The relative constancy in snow extent speaks to the resilience of Earth’s climate system, and challenges oversimplified predictions about the impact of climate change on winter snow cover…

So, don’t fret and I’ll see you on the slopes.

Irrational Fear is written by climatologist Dr. Matthew Wielicki and is reader-supported. If you value what you have read here, please consider subscribing and supporting the work that goes into it.

Read more at Irrational Fear

I am sure the Owners and Operators of our local Mt. Shasta Ski Park read the New York Slimes(All the Sludge that’s fit to Print) and got a goof laugh and their fake news

The imbecile who said CHILDREN WILL NEVER KNOW WHAT SH NW WAS needs to apologize for their idiotic Statement

I frequently read that “climate change is an indisputable reality”, even in anti-alarm articles such as this. But is a variable yet gradual warming trend resulting in an actual climatic change? A longer growing season lets me harvest more from my garden. Some years do offer a longer than average season, but others start later or end earlier, sometimes both. I’d be lying if I insisted that I noticed a change in the climate. Just because alarmists make that claim doesn’t mean that it’s true.

Same here. I’ve been farming most of my sixty-nine years and there is no perceptible weather trend. I consider 2010 and 2023 as ideal growing years. Circa 1970 we harvested a record-yielding crop of tomatoes for Campbell’s Soup. 1982 was the first time I planted corn, huge yield for the time. I will allow that the Great Lakes have a moderating effect where I live.

Equatorial alpine regions rely on the warmer months of the year for the bulk of their annual snowfall. During cold winter months the air is generally too dry to support snowy weather. It all makes sense but you have to think about these circumstances carefully to understand them