Crichton was a man of formidable intelligence and boundless curiosity, and those two qualities don’t go together quite as often as they should. For years, when I picked up his latest novel, I’d find myself sighing, “Of course.”

The books had the inevitability of all the truly great ideas – as if they had not been cooked up in his study but had always been lying there, like truffles out in the woods, and he’d just been the first hound to get to them and snuffle them out.

But very few hounds get to them again and again, for over thirty years: The Andromeda Strain, Congo, Rising Sun, Jurassic Park, Disclosure – which was #MeToo way back a quarter-century ago, and with a dreadful Demi Moore movie sale to boot.

Disclosure was the Number One bestselling novel of 1994, the same year Crichton had the Number One movie, Jurassic Park, and the Number One TV show, “E.R.”

To be sure, the characters and the prose didn’t always rise to life, but the concept, the premise, the hit title usually saw him through.

The critics were snippy about Crichton, but then he had the measure of the media far more than they had it of him.

I had a small amount of personal contact with him. A few years back I wrote a piece for The Australian about “climate change” and made a reference to his latest book:

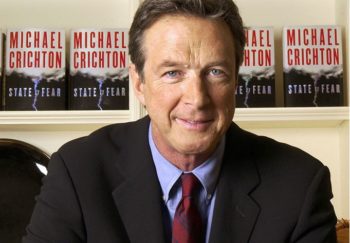

Michael Crichton’s environmental novel State of Fear has many enjoyable moments, not least the deliciously apt fate he devises for a Martin Sheenesque Hollywood eco-poseur.

But, along the way, his protagonist makes a quietly sensible point – that activist lobby groups ought to close down the office after ten years.

By that stage, regardless of the impact they’ve had on whatever cause they’re hot for, they’re chiefly invested in perpetuating their own indispensability.

That’s what happened to the environmental movement.

A day or so later I got an e-mail from him, thanking me not just for the endorsement but for the broader argument, and making a couple of very sharp, technical points about the “global warming” scare.

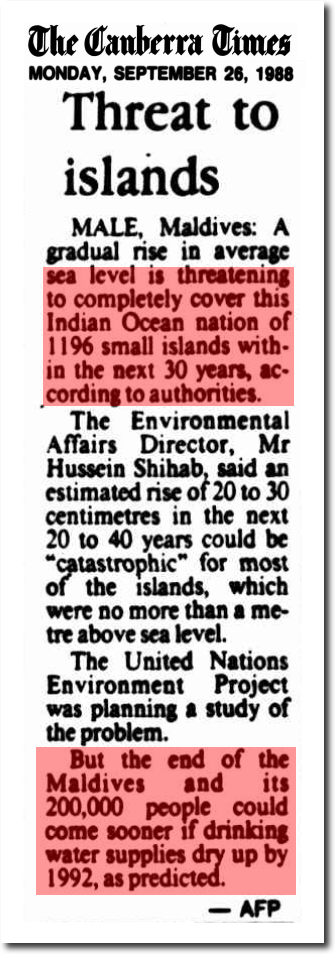

As soon as the eco-hooey piqued his interest, he accumulated a ton of information and marshaled it more effectively than most folks on either side of the debate. That was the way he worked.

Once a subject grabbed him, he soaked up far more factoids and graphs and pie charts than he could ever use in a novel. But they were part of the solid foundation from which his most inspired flights of fancy took off.

So State of Fear made him a lot of enemies because in today’s world the tastemakers prefer our artists to be ideologically compliant.

Thus his eco-dissent earned him a lot of snippy reviews of which the New York Times headline can stand for the whole bunch:

State of Fear: Not So Hot

Which was a pity. Because it meant the critics were disinclined to credit the last novel published in Crichton’s lifetime, Next.

By then – 2007 – he knew there would be no “Next” for him, but even so, it would make a grand title for his collected works.

He had a remarkable instinct not just for novelizing the hot topic du jour but for pushing it on to the next stage, across the thin line that separates today’s headlines from tomorrow’s brave new world.

He’s especially good at the convergence of the mighty currents of the time – the intersection of the technological, legal, political and cultural forces in society and the way wily opportunists can hop and skip from one lily pad to another until something that would once have sounded insane is now routine.

In Next, for example, a celebrity divorce attorney slumbering through a yawnsville meeting with some schlub cuckold of a genetic research exec suddenly spots the billable hours a wily trial lawyer can stack up over genetic testing in custody cases – and that’s before they’ve even identified half the genes worth litigating over.

The best Crichton novels are like the DNA double-helix – strands of science and media, genius and huckstering that twist in and out of each other.

To be sure, he was an airport novelist, in the sense that airport bookstores were piled high with his books.

By far the most conventional part of his books is the opening, in which a couple of low-life shamuses pursue a guy and a Ukrainian hooker through a landmark Vegas hotel or whatever – all payphones and chases through restaurant kitchens and frantic pushing of elevator buttons.

And it ends in death. It’s like reading a great description of some movie.

But where Crichton goes after that is all his own. In Next, for example, he appears to have foreseen one of the phenomena of the world a decade hence – bogus and manipulated Google search results.

He also anticipates what one might call the geneticization of life, including a “sociability gene” – formerly a “conventional gene” (i.e., it predisposes one to boringly conventional behavior) but that name didn’t focus-group well.

There is also a “Neanderthal gene”, to which environmentalists are prone:

Why, then, did Neanderthals die out? The answer, according to Professor Sheldon Harmon of the University of Wisconsin, was that the Neanderthals carried a gene that led them to resist change. ‘Neanderthals were the first environmentalists. They created a lifestyle in harmony with nature. They limited game hunting, and they controlled tool use. But this same ethos also made them intensely conservative and resistant to change.’

That was a bit of harmlessly low payback for those Big Climate bores who attacked Crichton for State of Fear, but even in the aside, one gets a sense of how unforgiving conventional progressivism is of those who wander even a little off the reservation.

Even his throwaways have big ideas, like this supposed press release from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology:

MIT scientists have grown a human ear in tissue culture for the first time… The extra ear could be considered ‘a partial life form – partly constructed and partly grown.’ The ear fits comfortably in the palm of the hand…

Several hearing-aid companies have opened talks with MIT about licensing their ear-making technology. According to geneticist Zack Rabi, ‘As the American population ages, many senior citizens may prefer to grow slightly enlarged, genetically modified ears, rather than rely on hearing-aid technology.

A spokesman for Audion, the hearing-aid company, noted, ‘We’re not talking about Dumbo ears. Just a small increase of 20 percent in pinna size would double auditory efficiency. We think the market for enhanced ears is huge. When lots of people have them, no one will notice anymore. We believe big ears will become the new standard, like silicon breast implants.’

Which, of course, is all too likely. Picture Florida circa 2025, a gated community full of big-eared nonagenarians.

And the implants line reminds you how easily we accept what would once have seemed downright creepy: cities full of women with concrete embonpoints that bear no relation to the rest of their bodies.

As one Crichton character says, he knows they’re fake and they don’t feel right but it turns him on anyway.

If you can accept, in effect, a technological transformation of something as central to human experience as breasts, why would you have any scruples about what technology can do in far more peripheral areas?

A decade ago, they found the usual unfinished manuscripts in his study, and then signed lesser men to finish them.

I liked the idea of one, another big-idea book about a very small idea, nanotechnology, but Micro wasn’t the same without the big guy.

He lives on, on the telly, in a show about living on and on and on, “Westworld”.

Yet I wish more novelists meandering through fey, limpid literary inconsequentialities would try books like Michael Crichton’s. But who knows? Maybe they lack the blockbuster gene.

Read more at Steyn Online

To many of the modern Eco-Wackos ENIROMENTALISM is their new age false religion they follow the trouble is they want to force us all to convert to their false religion just like with Islam and those who refuse should have their homes burned down