Readers will recall this story from January:

Scientist Brad Lister returned to Puerto Rican rainforest after 35 years to find 98% of ground insects had vanished.

“We knew that something was amiss in the first couple days,” said Brad Lister. “We were driving into the forest and at the same time both Andres and I said: ‘Where are all the birds?’ There was nothing.”

His return to the Luquillo rainforest in Puerto Rico after 35 years was to reveal an appalling discovery. The insect population that once provided plentiful food for birds throughout the mountainous national park had collapsed. On the ground, 98% had gone. Up in the leafy canopy, 80% had vanished. The most likely culprit by far is global warming.

“It was just astonishing,” Lister said. “Before, both the sticky ground plates and canopy plates would be covered with insects. You’d be there for hours picking them off the plates at night. But now the plates would come down after 12 hours in the tropical forest with a couple of lonely insects trapped or none at all.”

“It was a true collapse of the insect populations in that rainforest,” he said. “We began to realise this is terrible – a very, very disturbing result.”

Earth’s bugs outweigh humans 17 times over and are such a fundamental foundation of the food chain that scientists say a crash in insect numbers risks “ecological Armageddon”. When Lister’s study was published in October, one expert called the findings “hyper-alarming”.

According to the Lister paper:

Over the past 30 years, forest temperatures have risen 2.0 °C, and our study indicates that climate warming is the driving force behind the collapse of the forest’s food web…

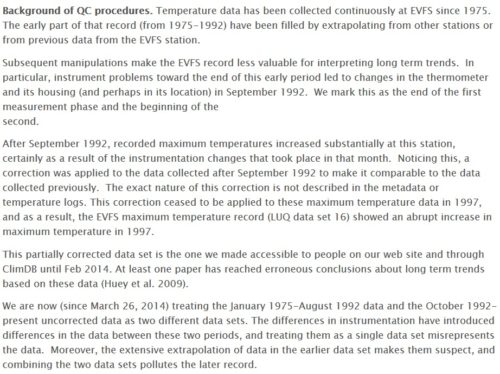

As I reported at the time, the supposed temperature increase was fake, an artifact of merging two sets of incompatible data.

The El Verde Field Station, responsible for the meteorological data, clearly warned against combining these two sets of temperature data, because the first one up to 1992 was artificially higher because of faulty equipment.

Any competent scientist should have double-checked the source of the data, but for some reason, Lister did not.

Now PNAS, which ran the original study, has published a new paper which rubbishes Lister’s findings.

Not only does this new study confirm the incompatibility of the temperature data, but it also questions Lister’s claims that insect populations are even declining at all:

In PNAS, Lister and Garcia (1) report declines in abundances of understory arthropods and lizards between 1976 and 2012 and claim similar declines in populations of arthropods, frogs, and insectivorous birds based on data from the Luquillo Long-Term Ecological Research project (LUQ). Their conclusion, that increasing temperature has led to a collapse of the food web, has attracted considerable attention from public media, but this conclusion is not corroborated by empirical evidence from LUQ (see Supplementary Materials, https://luq.lter.network/pop-trends-yunque-luquillo). Also, the authors fail to consider the effects of hurricanes and subsequent changes during secondary succession.

Lister and Garcia (1) interpret temporal changes in abundance of the walking stick (Lamponius portoricensis), canopy arthropods, frogs (Eleutherodactylus coqui), and birds at El Verde to be a consequence of increasing annual mean maximum daily temperature. In many cases, abundance data are not adjusted to consider variation in sampling effort. Moreover, the authors combine data files that are not compatible to create the temperature record for analyses. Indeed, maximum temperature from this record evinces a significant linear decrease at El Verde (cooling) in the period during which Lister and Garcia analyzed demographic data, a pattern evident in figure 1A of ref. 1 (see figures 1 and 2 of Supplementary Materials).

Using Lister and Garcia’s (1) analytical approach for temporal trends, we found a significant decline in density of Lamponius from 1993 to 2011, but density was not statistically related to temperature during this period (figures 3 and 4 of Supplementary Materials). These results contradict those of Lister and Garcia and suggest a more complex interplay of factors affecting variation in abundance of Lamponius (2). Canopy arthropod density does not decline between 1994 and 2009 but does increase significantly with increasing temperature (figures 5 and 6 of Supplementary Materials), even for the 10 most abundant taxa (tables 1 and 2 of Supplementary Materials), which Lister and Garcia claimed to have used (3).

Long-term data do not suggest a simple decline in adult frogs from 1987 to 2017 (figure 7 of Supplementary Materials) but do document an increase in numbers with increasing temperature (figure 8 of Supplementary Materials). Numbers vary in a consistent and nondirectional manner, except for short-term increases after Hurricanes Hugo and Georges, which modified habitat structure, followed by decreases to predisturbance levels (4) (figure S3B of ref. 1). Although prehurricane data exist for all 4 of Woolbright’s (4) plots, Lister and Garcia (1) do not include these data (figure S3A, C, or D of ref. 1). Stewart’s (5) data used by Lister and Garcia are consistent with this phenomenon [i.e., higher numbers after Hurricane David (1979)], followed by a decline to the typical range observed as recently as August 2017.

Lister and Garcia (1) do not consider the effects of changing forest structure following Hurricane Hugo (1989), which inflated avian captures rates at the beginning of the sampling period (6, 7). Their conclusion that the abundance of the insectivorous Puerto Rican tody (Todus mexicanus) declined by 90% is not supported by mist-netting data (capture rates from 1980 are similar to those from 2005) or point-count data from the same period (figures 9–11 of Supplementary Materials).

We found no evidence to support the conjecture that food webs are collapsing at LUQ as a result of warming. The narrow focus on temperature-related aspects of climate change as the causative agent does not address the multiple disturbances (e.g., hurricanes and droughts) that affect the forest (8).

https://www.pnas.org/content/early/2019/05/16/1820456116.full

Just for the record, this is the official description of the temperature dataset, as published by Luquillo LTER:

http://luq.lternet.edu/data/luqmetadata181

Read more at Not A Lot Of People Know That

The study cited wasn’t even junk science but down right fraud in order to support the climate change agenda.

Dave O is right, bugs like it warm. That is why there are a whole lot more of them in the jungles than other wet places such as the Olympic Rain Forest.

We see lots of bugs in the summer when its warm The Guardian is just another lying liberal rag

Pretty sure bugs like it warm just like other species.

They aren’t going anywhere except there will be a whole lot more of them. Which helps all the animals that feed on them, etc.