Later this week the Senate Budget Committee will hold a hearing on “the health costs of climate change.” …

Later this week the Senate Budget Committee will hold a hearing on “the health costs of climate change.” …

Projections of the future climate and its possible impacts on human health require the use of scenarios of the future — these scenarios underpin both (a) projections made by earth system models for variables such as future extreme temperatures and (b) projections made by integrated assessment and economic models for variables such as human mortality and associated damage. [emphasis, links added]

Such projections typically identify the effects of extremely high temperatures on human mortality as the most significant human health impact of climate change.

In turn, the projected human health impacts of future climate change are typically the dominant cost of climate change from such analyses and thus a key factor in derived quantities such as the social cost of carbon and the projected economic benefits of climate mitigation.

For instance, a recent paper by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) being used to support Biden Administration climate policies identified human health impacts driven by projected future changes in extreme temperatures as the overwhelmingly dominant factors in projected future costs of climate change, as you can see in the figure below.

The paper explains:

“national total damages in 2090 are primarily driven by the valuation of premature mortality attributable to climate-driven changes in extreme temperature (mean: $2.3 trillion per year; 95% CI: $0.31 – $9.9 trillion per year)”

The production of such claims is based on mind-numbingly complex methods that require considerable expertise and time to understand, much less replicate.

Here I suggest two straightforward questions that anyone can ask and answer of such methods to better understand how the numbers were produced. …

Question 1: What scenarios are used to produce the estimates?

As frequent readers here will well know, the choice of the scenario used in a climate projection can make the difference between an apocalyptic-looking future and one that appears much more manageable.

You won’t be surprised to learn that many, if not most, studies that project future public health impacts of climate change rely on extreme, implausible, or even impossible scenarios.

For example, a study that is central to the Biden Administration’s valuation of future climate damages — Carleton et al. 2022, which also plays a supporting role in the EPA study cited above — projects future impacts of extreme heat based on a scenario called SSP3-8.5.

You can see this in their figure and caption below (with the yellow highlight added by me).

Here is a very big problem with this analysis — SSP3-8.5 does not exist. You read that right. It is a contrived scenario that maximizes future impacts but is detached from both modeling and the real world.

I won’t get too far into the gory details, but here is how Justin Ritchie and I characterized this type of scenario misuse, which relies on combining a worst-case socio-economic scenario (SSP3) with a worst-case climate forcing (8.5 watts per meter squared):

The combination of SSP3 and RCP8.5 was considered implausible by the SSP developers . . . Since the RCP8.5 scenario was the worst-case for greenhouse gas concentrations among the RCPs, there is sustained motivation to study the climate impacts of such a high level of greenhouse gases.

Yet now the socioeconomics of the updated SSP5-8.5 indicate this climate forcing pathway is no longer truly a worst-case, because under the characteristics of the scenario the incredibly wealthy society which produces it could conceivably have ample resources to readily adapt to resulting changes in climate.

Thus, a growing body of research utilizes the implausible SSP3-8.5 chimera which projects a poor and vulnerable global society in a high climate impact environment.

Here is another example. To produce estimates of future climate damage, the Biden Administration’s EPA relies on scenarios generated by Resources for the Future (RFF). You can see below the range of global temperature and U.S. population scenarios for 2100 of the RFF scenarios.

You can see that these scenarios include a 2100 projected global temperature change that ranges from -3 Celsius (yes, that is minus) to an increase of 15 Celsius relative to 1995.

Similarly, the projected 2100 US population ranges range from near zero (zombie apocalypse?) to ~3.75 billion. You don’t have to be a climate scientist or a demographer to see some considerable ridiculousness in play here.

Yet, the resulting methodology used to convert scenarios into projected future health impacts takes averages across all these scenarios, giving outsized weighting to the most extreme values.

The result is projections far more extreme than if made using more plausible representations of climate and population futures.

Shown in the table below is the bottom-line result from the EPA analysis, which clearly shows that extreme assumptions are the handmaiden to extreme results.

The table shows that the mean result for U.S. damages from the EPA study lies between two scenarios now judged to be implausible (or if you prefer, “low likelihood” in the calibrated language of the IPCC) — SSP3-7.0 and SSP5-8.5.

Instead, the Framework Convention on Climate Change views SSP2-4.5 as an upper bound on the current global emissions trajectory, and our work suggests a mid-range scenario of SSP2-3.4, which is nowhere to be found in this analysis.

Extreme scenarios produce extreme results.

They also create a false impression of the benefits of mitigation, as they start from unrealistically high results. Climate policy discussions deserve more realistically grounded analyses. My advice: ask the question, what scenarios are you using to produce your results?

Question 2: How does your analysis factor in adaptation?

One of the most incredible success stories of science, technology, and policy over the past century has been the incredible progress around the world in improving adaptative capacity to weather and climate.

This success story rarely gets reported on but that makes it no less real. There is of course more to do and continuing efforts are needed to maintain the progress made to date.

One dirty little secret in most studies of the future impacts of climate change (and not just on the effects of changes in extreme temperatures) is that future adaptation to climate variability and change is simply left out of projections.

Assumptions are made that the climate will change, but people’s behavior will not. This is not how the real world works.

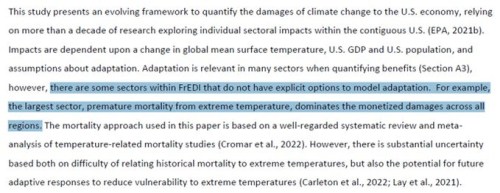

Consider the EPA study discussed above. Deep in the methods section, here is what it says about future adaptation to change, which it neglects to include in its methodology:

Why does adaptation matter? Consider the judgment of the World Health Organization on what happens to projections of the future impacts of extreme temperatures when adaptation is considered (emphasis added):

As expected, the estimates are reduced when adaptation is assumed, and the attributable mortality is zero when 100% adaptation is assumed.

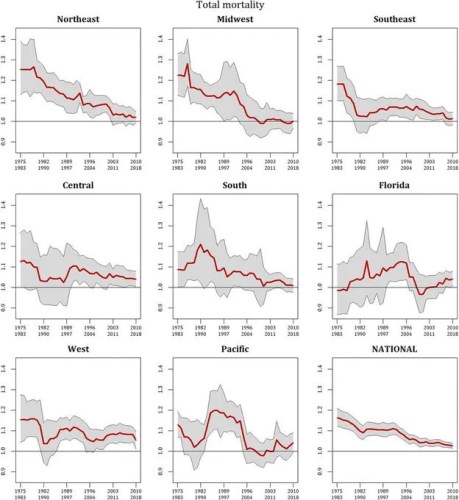

Of course, adaptive success may never reach 100%, but history shows that it can make a huge difference in outcomes, as shown in the figure below, which shows that U.S. heat mortality decreased dramatically almost everywhere over the past 50 years even as the incidence of [“extreme heat event” days] has increased. This is very good news.

Adaptation is not a substitute for mitigation, of course — they are complements. However, any study that purports to demonstrate the value of mitigation to the future effects of climate change without considering adaptation is flawed and potentially misleading.

As you interpret claims made about future climate impacts, always ask, how is adaptation considered in any analysis that seeks to project the future human health impacts of climate change?

Read the full post at The Honest Broker

The EPA under Clinton was a mess under Obama and bigger mess under Biden a Bottomless pit of waste and Globalism

“8.5 watts per meter squared” should read “8.5 watts per square meter”.

“… without considering adaptation is flawed and potentially misleading.”

“potentially”? It is intentionally ‘misleading’, and done with malicious aforethought.

Thank you Roger and CCD, a very good article…..

There are other sure fire indications of “malicious aforethought.” The climate model RCP 8.5 is acknowledged as extreme and unrealistic even among knowledge climate change advocates. So any time this model is being used, it is a sure sign of fraud. Another red flag for fraud is when only one side of an impact is considered. “The health costs of climate change” only considers deaths from excessive heat. Up to this point in history there have been many more deaths from the elderly not being able to adequately heat their homes. Both projections need to be considered.

From the BBC, 8 January, 2013:

More than 170 people have died in a cold snap sweeping across northern India, reports say.

The majority of deaths were in Uttar Pradesh state. Punjab and Haryana are among the other northern states badly hit by the cold weather.

Most of the deaths have been among the homeless and the elderly.

Last week the Indian capital, Delhi, experienced its coldest day for 44 years. Dense fog caused travel chaos with trains and planes delayed.

Reports say more people have lost their lives in the bitter cold in Uttar Pradesh and Uttarakhand states.

The Press Trust of India news agency reported that 175 people had died in Uttar Pradesh, India’s most populous state, where temperatures have dipped to below zero.

They are aware of “cold deaths”, but that doesn’t fit the current script.