If it’s climate change, you can pretty much guarantee the BBC won’t tell you the truth!

In fact, as with many deltas around the world, the problem has very little to do with rising seas, but soil subsidence:

Newswise — River deltas face threats other than rising sea levels. Physical geographer Philip Minderhoud (Utrecht University and Deltares Research Institute) has studied soil subsidence in the Mekong delta, and managed to raise the issue with the Vietnamese government. Minderhoud will defend his dissertation in University Hall at Utrecht University on 15 February.

In the late 1980s, Vietnam transitioned towards a market economy, which resulted in increased agricultural production, population figures, and urbanisation, all of which heightened the demand for groundwater. But as Minderhoud wrote in his dissertation, pumping out groundwater exacerbates the problem of soil subsidence. “The area also has a soft, shallow soil layer. The growth in infrastructure that has accompanied the past few decades of economic development has placed an extra burden on the soil. This is another reason the soil is subsiding, which makes the sea level rise more quickly in relation to the land. It’s as if the delta is sinking into the sea. Plus, saltwater is pushing ever farther land-inwards, so the delta also faces the problem of salinization.”

https://www.newswise.com/articles/the-sinking-mega-delta-in-vietnam-soil-subsidence-in-the-mekong-delta-is-a-hidden-assassin

Philip Minderhoud is regarded as the world’s leading expert on soil subsidence in the Mekong delta.

His paper, Impacts of 25 years of groundwater extraction on subsidence in the Mekong delta, Vietnam, notes that during the past 25 years, the delta sank on average ~18 cm as a consequence of groundwater withdrawal.

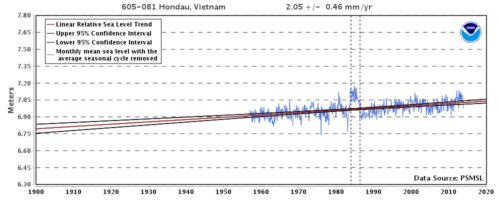

In comparison, a sea-level rise of 2mm per year is relatively insignificant.

https://tidesandcurrents.noaa.gov/sltrends/sltrends_station.shtml?id=605-081

The paper also states that over the past 25 years, groundwater exploitation has increased dramatically, transforming the delta from an almost undisturbed hydrogeological state to a situation with increasing aquifer depletion.

And it is not just water extraction:

Upstream damming and extensive mining of the Mekong’s riverbed for sand is causing the land between the sprawling network of rivers and channels near the mouth of one of the world’s great rivers to sink at a pace of around 2cm (0.75 inches) a year, experts and officials said…

Across the region, local authorities are struggling with a rapid pace of erosion that is destroying homes and threatening livelihoods in the Southeast Asian country’s largest rice-growing region.

A key cause is the years of upstream damming in Cambodia, Laos and China that has removed crucial sediment, local officials and experts said.

That sediment, vital for checking the mighty Mekong’s currents, has also been lost due to an insatiable demand for sand – a key ingredient in concrete and other construction materials in fast-developing Vietnam – that has created a market both at home and abroad for unregulated mining.

“It’s not a problem of the lack of water, it’s the lack of sediment,” said Duong Van Ni, an expert on the Mekong River at the College of Natural Resources Management of Can Tho University, the largest city in the Mekong Delta region.

At this time of year the waters of the Mekong used to flow into Vietnam as a milky-brown crawl, locals and officials said.

Now, the river runs clear. And without fresh sediment from upstream, the deeper riverbed creates stronger currents, which in turn eat away at the banks of the Mekong, where those who rely on the river for their livelihoods have their homes.

The problems began when China built its first hydropower plants in the Upper Mekong Basin, said Ni. That left Laos, Cambodia and Thailand as the main source of sediment for the Mekong in Vietnam, he said.

Sand mining in Cambodia boomed over the last 10 years, fuelled in part by demand from wealthy but cramped Singapore, where it is used to reclaim land along its coast, and culminating in a government ban of all Cambodian sand exports in 2017 under pressure from environmental groups.

But hydroelectric projects have continued. Earlier this month, Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen opened a US$816 million hydroelectric dam in Stung Treng province, near the border with Laos, built by companies from China, Cambodia, and Vietnam.

Unsurprisingly the BBC makes no reference to either of these factors but spends 10 minutes mentioning climate change every few seconds.

Read more at Not A Lot Of People Know That

It’s obvious the BBC is biased towards AGW/ACC, but in this case they purposely left out a very significant fact:

The people living in the Mekong have been pumping out ground water for years. The PRIMARY cause of increased tidal surge is NOT sea level rise, but ground subsidence due to the loss of ground water. At least 2 scientific papers put the average subsidence rate at between .5 – 1 cm/year for at least the last 25 years. Indeed, some parts of the Mekong delta have sunk almost 500 cm, or half a meter. As the Mekong is only a few meters above mean sea level (estimates range from .8 meter to 2.5 meters), subsidence has a huge impact on storm surge.

NOAA estimates the mean sea level trend for the Mekong is about 2.18 millimeters/year with a 95% confidence interval of +/- 0.71 mm/yr based on monthly mean sea level data from 1957 to 2001.

This is far less than land subsidence.

I would say it’s not sea-level rise OR land subsidence but it’s both. Therefore I would also avoid to mention it lying from anyone as both factors play a role and are important. Climate change causes sea-level rise indeed, but also a change in rainfall patterns. They have to be taken into account too. So: don’t say climate change is not an important issue, however: the impact of land subsidence is – at some places in the world – even more than that of sea-level rise only. We should not blame each other but collaborate.

Like i have said before the BBC is as bad as CNN its Propeganda not News