This paper has become a good example of media hype overwhelming actual substance. For example, take this headline from Doyle Rice at USAToday on April 13,

“A major climate boundary in the central U.S. has shifted 140 miles due to global warming”

So, what’s wrong with the headline? Nowhere in the original scientific study can I find any observational evidence of such a shift.

The fact is, the study is a modeling study — not observational. They tell us what might happen in the coming decades, given certain (and numerous) assumptions.

Since I’ve been consulting for U.S. grain interests for the last seven or eight years, I have some interest in this subject.

Generally speaking, climate change isn’t on the Midwest farmers’ radar because, so far, there has been no sign of it in agricultural yields.

Yields (production per acre) of all grains, even globally, have been on an upward trend for decades.

This is fueled mainly by improved seeds, farming practices, and possibly by the direct benefits of more atmospheric CO2 on plants. If there has been any negative effect of modestly increasing temperatures, it has been buried by other, positive, effects.

And so, the study begs the question: how has growing season precipitation changed in this 100th meridian zone?

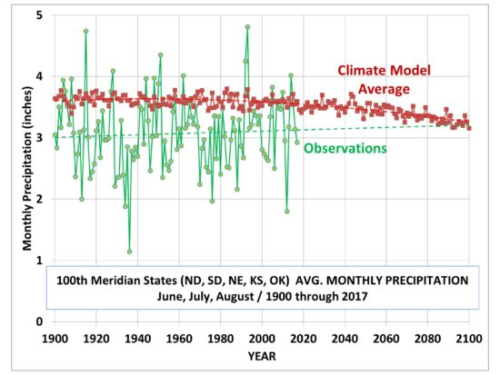

Using NOAA’s own official statewide average precipitation statistics, this is how the rainfall observations for the primary agricultural states in the zone (North and South Dakota, Nebraska, Kansas, and Oklahoma) have fared every year between 1900 and 2017:

Jun, July, August average monthly precipitation as observed over 5 U.S. states encompassing the 100th Meridian, and as predicted by a CMIP5 (RCP8.5 forcing scenario) multi-model mean from 35N to 50N, and 95W to 105 W (observational data from https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/cag/statewide/time-series; model data from https://climexp.knmi.nl/selectfield_cmip5.cgi?id=someone@somewhere)

What we see is that there has been, so far, no evidence of decreasing precipitation amounts exactly where the authors claim it will occur (and according to press reports, has already occurred).

To the authors’ credit, in their final “Discussion and Conclusions” section of the research paper they admit:

“First, we have shown that state-of-the-art models simulate the aridity gradient across North America poorly.”

“Second, while current Earth system models predict widespread declines in soil moisture and increases in continental aridity, they also simulate increases in net primary productivity.

This is because, within the models, the beneficial effects on photosynthesis and water-use efficiency of increased CO2 overwhelm the effects of increased temperature and vapor pressure deficit.” (emphasis added)

The positive effects of more CO2 on global agricultural yields have been tallied, as I have previously discussed here.

Yet, the popular press emphasizes the alarmist nature of the article, even going so far as to make as the central claim something that, as far as I can tell, isn’t even in the paper (!)

Read more at Dr. Roy Spencer’s Blog

Gregory Wrightstone covered this very topic quite well in his recent book, “Inconvenient Facts”. Higher CO2 concentration means the plant does not need to have its stomata open as long to absorb the needed CO2 so it loses less moisture. This will then keep the ground moister since the plant won’t need to take up as much water from the soil.